Warhol and Prince: Redefining Fair Use

In a highly consequential decision involving signature works of renowned artist Andy Warhol and photographs of music legend Prince, the U.S. Supreme Court has clarified the long-standing fair use defense to copyright infringement and narrowed the scope of transformative works that qualify as fair use. The decision in Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith squarely addresses the decades-long uncertainty over the definition of “transformative” and inconsistent application of the fair use doctrine, thus strengthening and enhancing copyright protection for artistic works.1

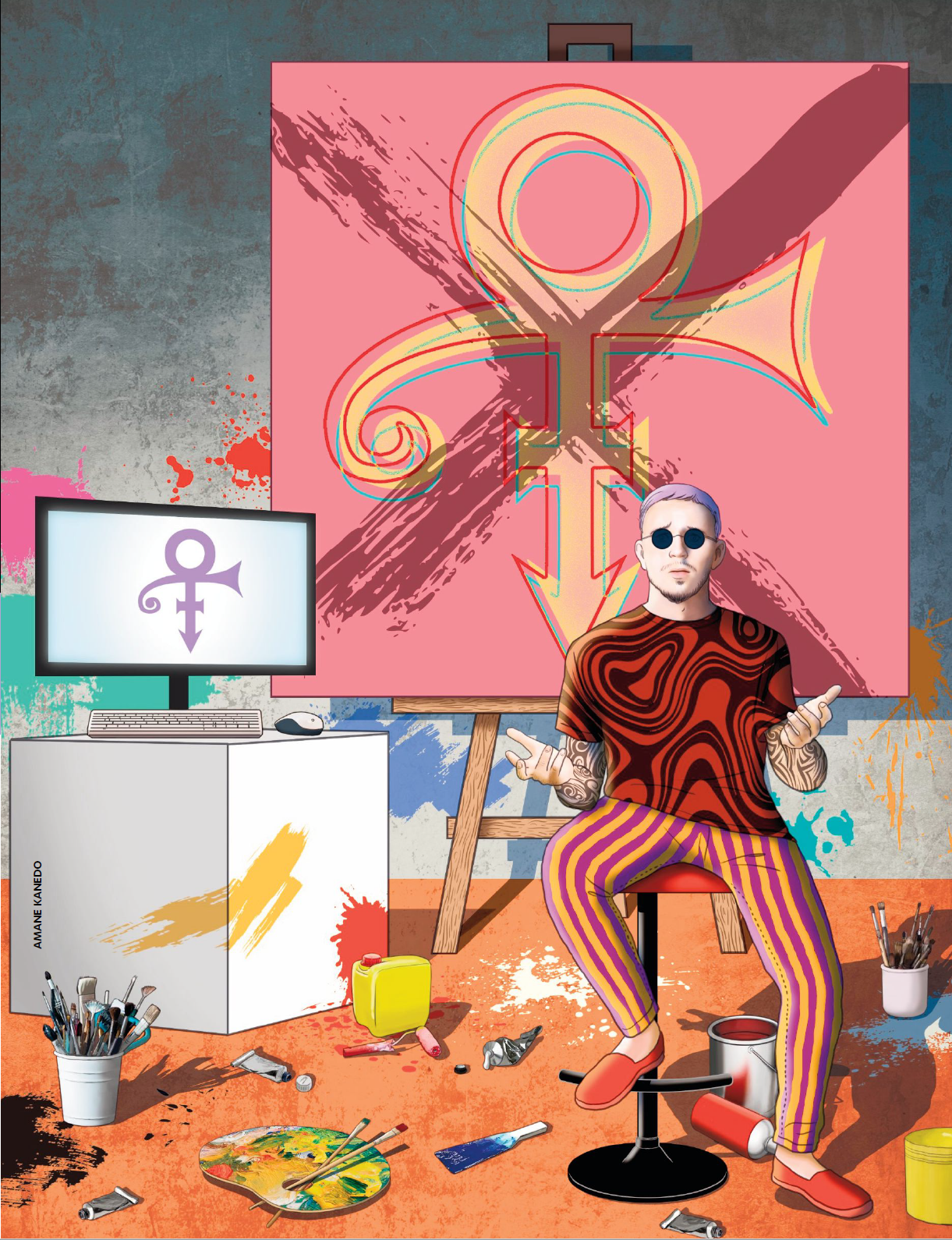

The backdrop of the Supreme Court decision in Warhol begins in 1981, when a young future music legend Prince submits to being photographed for a Newsweek magazine article by photographer Lynn Goldsmith, who shoots a number of such photos of Prince (“Prince Photos”).2 Then in 1984, Vanity Fair decided to do an article on Prince, who by then was well on his way to fame, and hired Warhol, who is perhaps best known for creating silkscreen images of contemporary celebrities and the design of the Campbell soup can.3Warhol’s task was to work his “silkscreen” style on one of the photos taken by Goldsmith for the article. The article duly credited Goldsmith as the source of the photo reworked by Warhol.4

Photographs have long been considered creative works and protectible under copyright law.5 The protectible, original elements of a photograph include posing the subjects, lighting, angle, selection of film and camera, evoking the desired expression, and almost any other variant involved.6 However, copyright does not protect ideas or concepts and, therefore, the photograph’s idea or the photographer’s choice of a given concept are not protectible.7 The Warhol dispute centered on this well-established principle of copyright law.

The dispute originated when, following completion of his work on the Vanity Fair project, Warhol created a series of images

in his signature silkscreen style (the “Prince Series”) based on the Goldsmith Photo. The Prince Series was subsequently copyright registered by Warhol’s foundation (AWF), which was created after Warhol’s death in 1987, without providing any credit to Goldsmith. Then, in 2016, following Prince’s death, Vanity Fair decided to devote an issue commemorating Prince’s life and obtained a license from AWF to one of the Prince Series images for the magazine cover. It was at this point that Goldsmith first became aware of the Prince Series and contacted AWF to complain about AWF’s unauthorized use of her work.

In response to Goldsmith’s complaint, AWF initiated a lawsuit against her, seeking a declaratory judgment of non-infringement or, in the alternative, fair use. In this context, copyright infringement hinges on whether the works are substantially similar.8 Arguing, first of all, that the Prince Series was not substantially similar to the Goldsmith Photo, AWF also asserted that, even if it was, it constituted fair use of Goldsmith’s Photo and was thus exempt from a copyright infringement claim by Goldsmith. The district court granted summary judgment in favor of AWF on its fair-use claim, finding the Prince Series to be sufficiently “transformative” so as to not constitute a “derivative” of the Goldsmith Photo. The decision explained that the two images conveyed very different feelings to viewers—while the Goldsmith Photo conveyed an image of a shy, aloof individual, Warhol’s rework conveyed one of an iconic, larger-than-life figure.9

However, the Second Circuit Court of Appeal reversed, concluding that Warhol’s creation was closer to a derivative work than a transformative work. The Supreme Court affirmed the court of appeal, ruling that the similarity of the use of two works as well as their commercial nature weighed against a finding of fair use.

Fair Use Doctrine

The copyright statute awards an owner of a copyrighted work the exclusive rights to the work itself and to any “derivative

works based upon the copyrighted work.”10 At the same time, the law recognizes that certain uses of an otherwise protected work are permitted as “fair use” of that work. The history of fair use in the copyright context goes back to the beginning of copyright protection laws, when courts recognized “some opportunity for fair use of copyrighted materials has been thought

necessary to fulfill copyright’s very purpose, to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts.”11 In a decision made back in

the middle of the nineteenth century, Justice Joseph Story warned against over-enforcement of copyrights, noting that “in truth, in literature, in science and in art, there are, and can be, few, if any, things, which in an abstract sense, are strictly new and original throughout. Every book in literature, science and art, borrows, and must necessarily borrow, and use much which

was well known and used before.”12

At common law, courts analyzed whether a work qualified as fair use by “looking to the nature and objects of the selections

made, the quantity and value of the materials used, and the degree in which the use may prejudice the sale, or diminish the profits, or supersede the objects, of the original work.”13 That standard was later codified in the 1976 Copyright Act, which provided a limited “fair use” exception to such exclusivity, so that “the fair use of a copyrighted work…for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching…, scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright.”14

Under current law, Section 107 of Title 17 in the U.S. Code is the starting point for determining whether use of a copyrighted work is considered fair use. Under Section 107, to determine a use as fair use, courts evaluate these four factors: 1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes; 2) the nature of the copyrighted work; 3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and 4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.15

Defining “Transformative”

In Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc.,16 the Supreme Court saw fit to emphasize the value of transformative work for its role in furthering the promotion of science and the arts, which places such works “at the heart of the fair use doctrine’s guarantee of breathing space within the con fines of copyright.”17 Campbell tied fair use to the first of the four fair use factors set forth in Section 107, i.e., “the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature” and explained that “the enquiry focuses on whether the new work merely supersedes the objects of the original creation, or whether and to what extent it is “transformative,” altering the original with new expression, meaning, or message.”18 In that regard, the decision instructed that “the more transformative the new work, the less will be the significance of other factors, like commercialism, that may weigh against a finding of fair use.”19 As noted by the high court, the significance of a transformative work conveying a sufficiently different character, expression, meaning, or message is enough to exempt it from the reach of copyright infringement.

As directed by the above standard, the focus of the fair use inquiry by courts in the Warhol decisions should have been whether Andy Warhol’s rework of the Prince Photo merely superseded the objects of the original creation and supplanted it

or whether the rework created something new with a different purpose or character

than that of the original.

Warhol—Pre-Supreme Court

Despite the Supreme Court’s guidance, the inconsistency in the application of the fair use doctrine has remained, evidenced

by the lower court decisions in Warhol. As noted above, after Goldsmith became aware of the Vanity Fair article on Prince

following the death of the artist in 2016, she objected to AWF’s use of the Prince Series photo without her authorization, n response to which AWF filed suit against her. The district court, applying the standard set forth by the Second Circuit Court of Appeal in Cariou v. Prince, found the Prince Series to be transformative. According to that standard, “If looking at the works side-by-side, the secondary work has a different character, a new expression, and employs new aesthetics with creative and communicative results distinct from the original, the secondary work is transformative as a matter of law.”20 The court concluded that the standard applied to the Warhol case because the Goldsmith Photos focused on depicting a particular image of Prince as “not a comfortable person” and a “vulnerable human being,” while “Warhol’s Prince Series, in contrast, can reasonably be perceived to reflect the opposite.”21 That distinction, the court concluded, was sufficient to qualify the Prince

Series as transformative.

The Second Circuit reversed, stepping back from Cariou, by referring to that decision as the “high-water mark of our court’s recognition of transformative works” and one that “has not been immune from criticism.”22 The opinion went on to reject what the Second Circuit described as the district court’s “formulaic approach” to analyzing whether a work is transformative, in favor of a “context-sensitive inquiry that does not lend itself to simple bright-line rules.”23 Focusing on the comparison of the two works to determine whether Warhol’s rework of the Gold smith Photo was transformative, the Second Circuit found the rework in sufficient to qualify as transformative. Instead, the Second Circuit, analogizing to a film adaptation of a novel, noted that despite expected significant differences between the two works, e.g., plot lines, scene modifications, dialogue, and so forth, the film would still be considered an adaptation of the original and thus “identified as a paradigmatic example of derivative works.”24

The Supreme Court Decision

The Supreme Court granted writ of certiorari and upheld the Second Circuit’s decision, finding Warhol’s work did not qualify as transformative and thus fair use. The high court did not base its conclusion on all four fair use factors, as the Second Circuit had done, but only on the first prong of the test, namely, the purpose and character of the works, asking whether the use adds something new, with a further purpose or different character to the extent that the work can be considered transformative.25

Applying that standard, the decision noted that reworks frequently do add something new and have a further purpose compared with the original work, and thus the focus of the purpose and character inquiry should be on “whether and to what extent” the use at issue has a purpose or character different from the original. With the framework of analysis thus set up, the high court pointed out that a typical use of a celebrity photograph is its use with stories about the celebrity in publications often in magazines and to license their works to create derivative works as Goldsmith had done with the photo of prince at issue and that, in that context, the purpose of the images of Goldsmith and AWF were substantially the same in that both were portraits of Prince used in magazines to illustrate stories about Prince.26

By setting up the framework of analysis as such, the majority clearly reflected its reluctance to expand the scope of “transformative” at the expense of “derivative” works, which it worried would swallow the copyright owner’s exclusive right to

prepare derivative works. The decision provided an example to make the point, noting that a commercial remix of Prince’s “Purple Rain” that “added new expression or had a different aesthetic” or an adaptation of Alice Walker’s The Color Purple— by adding images, performances, original music, and lyrics—would not in themselves dispense with the need for licensing.27 In that regard, the concurring Supreme Court opinion pointed to the statutory language of Section 106, under which derivative works belong to the copyright holder of the original, while transformative works defined under Section 107 are outside the range of protection afforded to the copyright owner of the original work.28 The concurring opinion noted that expanding the scope of transformative to include derivative works would make “nonsense” of the statutory design.29

Another key aspect in the Supreme Court’s analysis of whether the later work in Warhol qualified as transformative was the finding that the Goldsmith Photo was a “recognizable foundation” for Warhol’s rework. In that regard, the decision concedes

that Warhol’s “modifications” to the Goldsmith Photo did alter some aspects of the original in a manner that resulted in the two works’ conveying different impressions to viewers. However, the opinion then points out that Warhol’s rework of the Goldsmith Photo nonetheless retained the essential elements of its source and, at the end, the Goldsmith Photo remained the recognizable foundation for Warhol’s rework. The Supreme Court ultimately dismissed AWF’s argument that the Prince Series was “immediately recognizable as a Warhol” pointing out that considering that fact in the analysis of fair use would create a “celebrity-plagiarist privilege.”30

The Dissenting Opinion

The dissenting opinion in Warhol, penned by Justice Kagan and joined by Chief Justice Roberts, focused its argument on the aim of the fair use doctrine to promote and foster creativity and that the constitutionally recognized goal of copyright, i.e., to promote science and the arts, was generally furthered by the creation of transformative works. The minority decision thus advocated a broader, more inclusive standard for determining whether a later work is transformative of an earlier one that would consider “whether the new work merely supersedes the objects of the original creation or instead adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message; it asks, in other

words, whether and to what extent the new work is transformative.”31

A key aspect of the high court’s analysis of whether a work qualified as transformative was the frame of reference of the two works vis-à-vis each other. In other words, the question is which work is the reference to which the other is to be compared to make that determination? The Andy Warhol Foundation urged the court to focus on the purpose that the creator of the original work, in this case Goldsmith, had in mind at the time the work was created, as well as the character of that work, and to compare that with the purpose of use of the later work. The foundation argued that with that frame of analysis, Goldsmith’s idea was to present a certain image of Prince with her photography and that Warhol’s later work had transformed that image from the vulnerable, uncomfortable person depicted in Goldsmith’s Photo to an iconic, larger-than-life figure. According to AWF, because the purpose and character of Warhol’s work is so different from Goldsmith’s, the first fair-use factor favors finding Warhol’s rework transformative.

Goldsmith, on the other hand, urged a frame of analysis that would be based on the purpose and character of the creator of the later work as the point of reference and argued that from that perspective Warhol’s intent in creating silkscreen images of Prince was to commercialize and monetize them. Thus, both works sought to and did license the respective images to a magazine looking for a depiction of Prince to accompany an article.32

The decision clearly indicates the majority’s agreement with the latter framework and reflects a view of fair use in which a secondary work that does not obviously and significantly possess a purpose different from the original would have difficulty qualifying for fair use as a “higher or different artistic use.” Rather, the secondary work contemplated by the Supreme Court majority itself must reasonably be perceived as embodying an entirely distinct artistic purpose, one that conveys a “new meaning or message” entirely separate from its source material. Therefore, altering or recasting a work with a new aesthetic will not do.33 The Supreme Court majority thus instructed that the judge needs to examine whether the secondary work’s use of its source material is in service of a “fundamentally different and new” artistic purpose and character, such that the secondary work stands apart from the “raw material” used to create it. The high court, comparing the two works side-by-side, concluded that the Prince Series is not “transformative” within the meaning of the first factor.

In that respect, the Supreme Court noted that Warhol’s rework of the Goldsmith Photo had largely involved re moving certain elements from the Goldsmith Photo, such as depth and contrast, and embellishing the flattened images with “loud, unnatural colors.”34 The opinion found the Warhol rework to be much closer to presenting the Goldsmith Photo in a different form, that form being a high-contrast screen-print, than to being work that makes a transformative use of the original, noting that the rework had retained the essential elements of the Goldsmith Photo without significantly adding to or altering those elements.35

Accordingly, the decision concluded that “If an original work and secondary use share the same or highly similar purposes, and the secondary use is commercial, the first fair use factor is likely to weigh against fair use, absent some other justification for copying.”36

Likely Impact of Warhol

The Warhol decision will have a profound impact on works that qualify as fair use and thus are eligible to escape the reach of copyright infringement laws. The decision is a boon to artists who can now retain rights to a much broader range of newer works that are based on their copyrighted works as derivative works.

Courts seeking to apply the Warhol decision are likely to find the concurring opinion of Justice Neil Gorsuch helpful. The concurring opinion instructs that the “transformative” inquiry should look at the particular use of the challenged work and assess whether the purpose and character of that use is different from that of the original.37 The standard set by Justice Gorsuch is appealing because it is clear and straightforward to apply in that its focus is “on how and for what reason a person is using a copyrighted work in the world, not on the moods of any artist or the aesthetic quality of any creation.”38

1 Andy Warhol Found. for Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 143 S. Ct. 1258 (2023).

2 Id.

3 Id.

4 Id.

5 Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, 111 U.S. 53, 60 (1884).

6 Rogers v. Koons, 960 F. 2d 301, 307 (2d Cir. 1992).

7 Bill Diodato Photography, LLC v. Kate Spade, LLC, 388 F. Supp. 2d 382, 392 (S.D. N.Y. 2005).

8 Shaw v. Lindheim, 919 F. 2d 1353, 1356 (9th Cir. 1990).

9 Andy Warhol Found. for Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 382 F. Supp. 3d 312, 326 (S.D. N.Y. 2019).

10 17 U.S.C. §106.

11 Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569, 575-76 (1994).

12 Emerson v. Davies, 8 F. Cas. 615, 619 (C.C.D. Mass. 1845) (No. 4,436).

13 Folsom v. Marsh, 9 F. Cas. 342 (C.C.D. Mass. 1841) (No. 4,901).

14 17 U.S.C. §107.

15 Id.

16 Campbell, 510 U.S. at 579.

17 Id.

18 Id.

19 Id.

20 Cariou v. Prince, 714 F. 3d 694, 707-708 (2d Cir. 2013).

21 Andy Warhol Found. for Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 382 F. Supp. 3d 312, 326 (S.D. N.Y. 2019).

22 Andy Warhol Found. for Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 11 F. 4th 26, 38 (2d Cir. 2021).

23 Id.

24 Warhol, 11 F. 4th at 39-40.

25 Campbell, 510 U.S. at 579.

26 Andy Warhol Found. for Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 143 S. Ct. 1258, 1278-80 (2023).

27 Id. at 1282.

28 Id. at 1289-90.

29 Id. at 1285.

30 See generally id.

31 Id. at 1288-89.

32 Andy Warhol Found. for Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 992 F. 3d 99, 113 (2d Cir. 2021).

33 Andy Warhol Found. for Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 382 F. Supp. 3d 312, 326 (S.D. N.Y. 2019).

34 Warhol, 992 F. 3d at 113-115.

35 Warhol, 143 S. Ct. at 1261.

36 Id. at 1277.

37 Id. at 1289.

38 Id.